Running technique: 3 reasons why runners develop shin splints and 7 ways to fix them

/I really dislike the term "shin splints." Probably more than you dislike actually having pain from shin splints. That's because the term has been used to describe about five different problems that occur in the lower leg. It's terribly vague.

The term "shin splints" has been applied to injuries that are more specifically described as medial tibial stress syndrome, tibial stress fractures, and exertional muscle pain. Exertional muscle pain is the most common type of problem, so for the sake of this article, I will refer to the shin muscle and tendon pain from exertion as “shin splints."

One of the shin muscles is the anterior tibialis, which is the biggest muscle on the front of your shin region. It’s main function is to pull the front of your foot upward. That's called dorsiflexion (see photo). It's helped by the neighboring extensor hallucis longus (EHL) and extensor digitorum longus (EDL) muscles.

While walking and running, they keep you from catching your foot and toes on rugs, roots, stones, steps, and generally rough surfaces. We’ve all caught a toe, tripped, fallen and groaned in pain as we lie on the ground. These are the muscles you can thank for keeping you from biting it everyday.

There are several reasons why runners will develop exertional shin splints. Some of them include:

Heavy reliance on heel striking. This is the most likely reason a runner, especially a new runner, would develop shin muscle overuse pain. With a heel strike, you must increase use of the anterior tibialis muscle or your foot will slap down to the ground. Runners who heel strike demonstrate a greater dorsiflexion (pointed up) angle upon ground contact compared to a runner who lands with their entire foot flatter or on their forefoot.

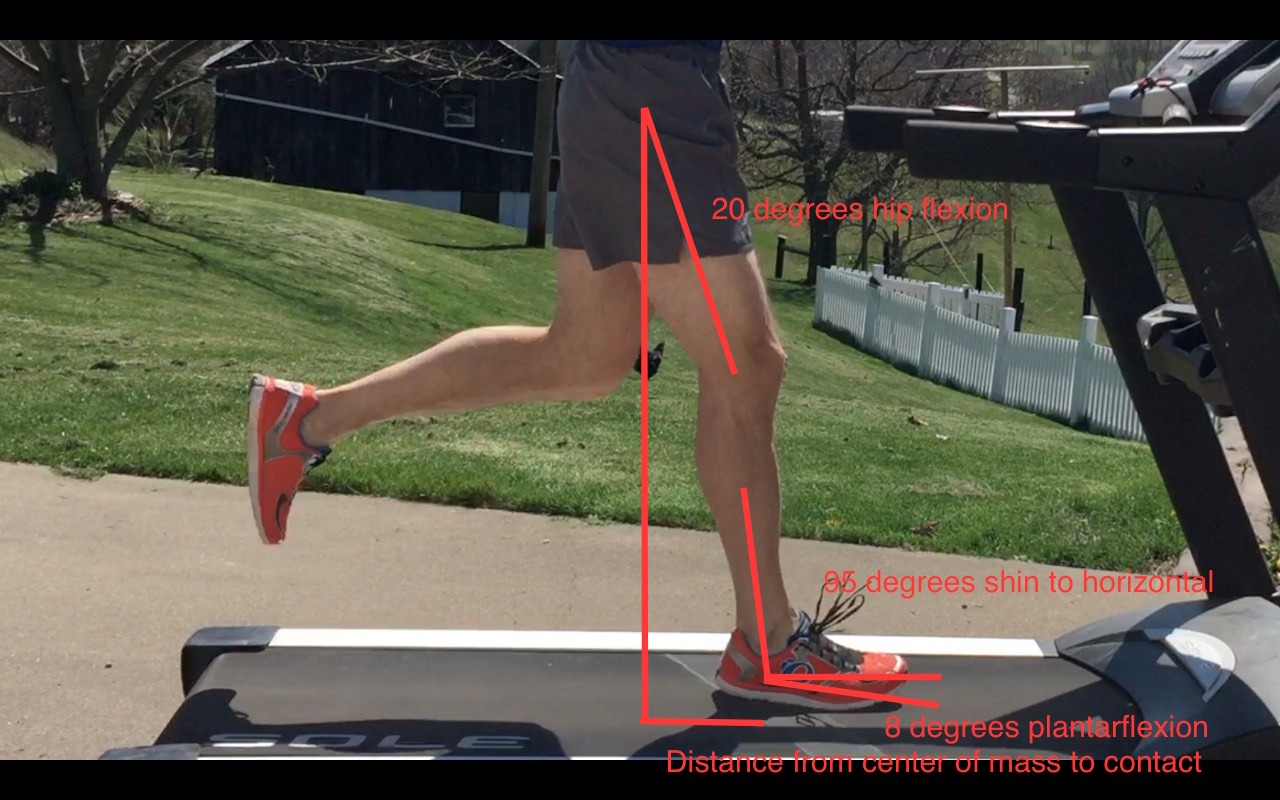

In the picture below the ankle is pulling up into dorsiflexion 15 degrees above a neutral ankle position. This is in contrast to the midfoot strike images below where the foot is contacting the ground in a slightly plantarflexed (pointed down) angle. In order to lower the front of the foot to the ground from a heel striking position, the anterior tibialis muscle needs to work extra hard. All of that extra work results in a chronic state of overuse in the shin muscles and tendons, which is easy to imagine when you are asking them to perform 700 contractions per mile.

Initial contact with heel strike pattern

Overstriding in the forward direction. Along with the heavy heel striking pattern, reaching the leg too far forward with each step will increase the stress on the shin muscles. You can use a heel strike pattern without causing shin splint pain if your foot contacts close to your center of mass. Imagine your center of mass being a line drawn straight down from the center of your hips, as in the following picture. If the foot contacts the ground 12 inches in front of the line instead of 10 inches, the demands are much different on the muscles, tendons and joints.

Most runners who shorten their stride in the forward direction start to land on their midfoot instead of their heel. Compared to the heel strike picture above, using a midfoot or forefoot strike pattern (and sometimes a slightly quicker turnover) causes the stride to be slightly shorter in the forward direction. That's evident with the lower hip flexion degree value. But it's most noticeable that the distance line to the point of contact at the bottom of the picture is clearly shorter than in the previous heel striking picture. It is possible to make an initial contact at this same closer point and use any of the three types of contact patterns.

Initial contact with midfoot strike pattern

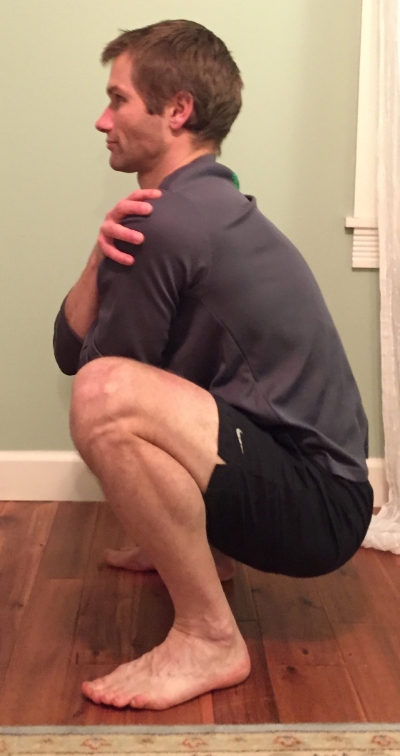

Short/tight calf muscles. If the muscles on the back of your lower leg are so short that you can’t take your ankle into the normal level of upward dorsiflexion motion, the shin muscles are going to need to work harder to overcome that passive resistance. One quick way to assess whether the muscles on the back of the lower leg are too short is to do a full squat. Barring any unusual knee or ankle joint and bone issues, if the feet can't stay flat on the floor, especially without turning the feet out or the arches collapsing, you may have a limitation in the length of those muscles.

Tips for correcting these issues.

1. In the cases of both heel striking and overstriding, the solution is much the same. The foot needs to land closer to your center of mass. You could simply think about taking shorter steps. You can think about it landing directly beneath you (which will never actually happen). A one-inch change in the initial contact point is going to feel like a 12-inch change but I assure you that the awkward feeling is normal at first.

2. Some runners need an external focus to prevent overstriding forward, so matching their cadence to the beat of a metronome can be helpful. Count the number of steps you take with one leg in one minute of running. Those who overstride are often taking less than 82 steps each minute. The metronome can be set for a value greater than 82 while you try to match the step rate with one leg.

3. For tight calf muscles, everyone’s first thought is “stretch.” Stretching is fine if you hold the stretch for at least 1 minute but 2-3 minutes is more effective to mechanically lengthen these tissues. And you would have to do it daily for at least a month to get much change. It can be more effective to perform soft tissue work with a foam roller, massage stick, tennis or lacrosse ball, massage therapist, or manual therapy from a Physical Therapist. Regardless, just try something! Lessons on muscle rolling here.

4. Relax the anterior tibialis muscle with consistent soft tissue maintenance. Trigger point dry needling or myofascial release can work wonders to make the muscle happy and decrease pain quickly. The massage stick can be great too. Lessons on muscle rolling here.

5. Practice engaging the anterior tibialis muscle by walking on your heels for 30-60 seconds continuously each day. Preferably after your symptoms have calmed down a bit.

6. Progressively increase your mileage. Going for a 4 mile run after a month of no running is a huge training error. Sometimes those muscles just need to be conditioned correctly.

7. Try a different shoe with a lower heel height. Pair this with the other solutions. A thicker heel can mean greater shin muscle load. And that thick heel is often the reason people heel strike hard in the first place.

If you battle repeatedly with shin splints, consider having a thorough running technique and gait evaluation. Yes, I can get the pain to go away easily with a couple treatments but don’t you want to keep it away permanently? A couple of small changes can mean a huge difference in your pain onset.

I can be reached at derek@mountainridgept.com if you have any questions.

Please share this article with your running friends! To receive updates as each blog comes out, complete the form below. I can be reached at derek@mountainridgept.com if you have any questions.