Are you bonking?

/Anyone who exercises for an extended period is at the mercy of their stored energy and blood sugar levels. Glucose is the basic sugar circulating in the bloodstream and it is well controlled within a specific range for a healthy person. Stored sugar, glycogen, from your liver and muscles, can be used to keep the blood glucose regulated.

If your blood sugar decreases to lower levels during prolonged activity and can’t be stabilized, your brain will prioritize itself over anything else because glucose is its primary fuel source. This means working muscles are not exactly high on the list. You are in the process of bonking, otherwise known as non-diabetic hypoglycemia or exercise-induced hypoglycemia.

Risk of bonking increases with the following:

- Longer duration of exercise

- Higher exercise intensity

- Exercise in a hot environment

- Insufficient calorie intake during the day of exercise

- Chronically insufficient calorie intake over a period of days

- Insufficient recovery time from a prior bout of exercise or multiple days of exercise as it takes nearly a day to restore glycogen after it has been used (in ideal conditions)

- Another recent episode of bonking

- Dehydration

- Limited prior exposure to depleting exercise

- Athlete inexperience

Athletes are not always aware of the signs and symptoms of bonking until they become more dramatic. Some symptoms of the blood sugar drop are mental and others are physical. The initial cues can be subtle but the symptoms can progress to more severe levels rapidly. Many marathoners know this as the feeling of “hitting a wall” around mile 18 to 20.

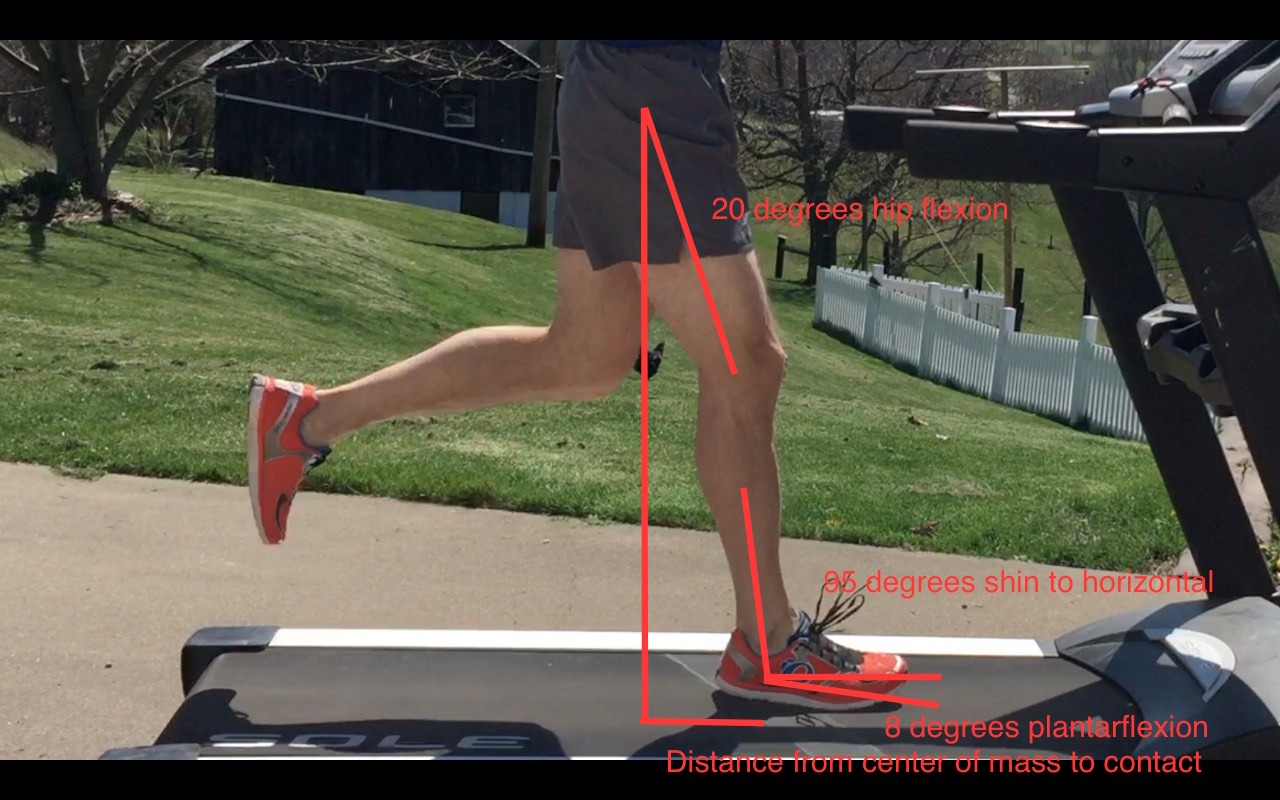

When bonking, pace per mile might initially change by something small, like 15 or 20 seconds. But if the effort continues and no calories are consumed, you could easily slow by 1-5 minutes per mile or even more.

I’ve known many hard-working, well-trained marathoners that train months for an “A” race, doing tons of distance and maybe even trained up to 23-26 miles. They feel strong but depleted at the end of those long training runs but they train more slowly than they race. So by running faster in the actual race they burn through their energy stores sooner and completely crash despite decreasing mileage for several days in advance of the marathon. That’s tons of training wasted because they refused to learn to eat a little something in the marathon.

Bonking happens around the same point for most people because we all store similar amounts of glycogen that are used up at similar rates. It’s possible that years of training could allow someone to burn a greater percentage of fat for energy, but harder efforts always require higher glycogen dependence. And having run for just a couple years isn’t long enough to perfect a fat burning metabolism.

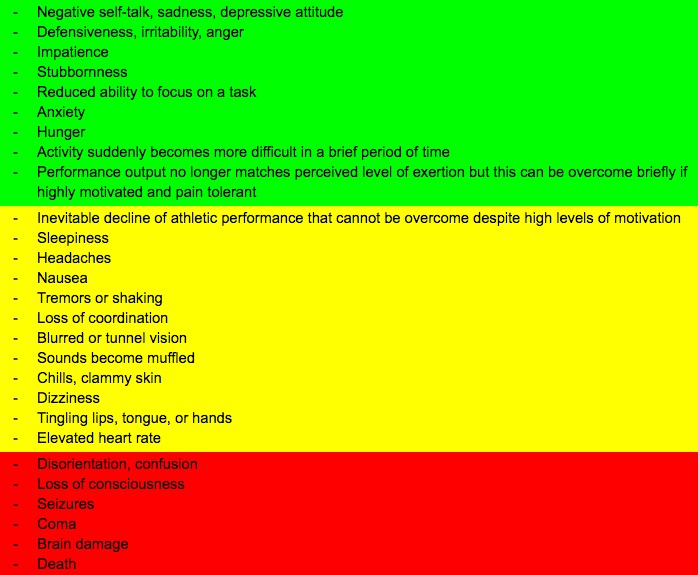

The signs and symptoms of declining blood sugar, in a general classification order of increasing severity:

Your job is to detect symptoms as soon as possible in order to keep your state from declining further. Ignoring the symptoms and hoping for the best is never going to end well. If you have signs and symptoms consistent with the green items, there’s a good chance you can pull things back together if you take appropriate action, though it won’t be a day of personal best performances.

A few experienced and lucky athletes might be able to come back quickly from the yellow zone but nobody is bouncing back from the red zone. Only the more stubborn people will even push themselves far into the yellow zone. It’s a super dangerous, slippery slope. Don’t do it. You can’t win against physiology.

Many people don’t have the motivation to put themselves deep into the pain cave, so they just automatically slow down in order to feel better when they feel uncomfortable and have persistent negative thoughts. Kudos to you for not being a ridiculously stubborn fool like some of us!

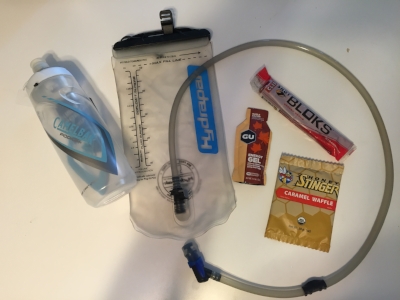

Simply slowing down may be sufficient to finish out the workout or competition. If you don’t want to slow down, then you need to eat something containing carbohydrates as soon as possible. Ideally this would be something with simple and complex carbohydrates. There are receptors in your mouth that detect sugars and just the act of eating can immediately reduce the brain’s stronghold on protecting you… from you.

But there’s a good chance that you need to slow down AND eat something, depending on how long you are planning to exercise. If you are bonking after 90 minutes and planned to be active for 3-4 hours then it’s going to be unreasonable to sustain the same effort without eating many more calories.

Three truths about bonking:

- You have to learn to eat during prolonged activity, even though you often won’t feel like eating, or the bonk will occur.

- If you don’t eat and your intention is to maintain both a high intensity and a prolonged duration of greater than 2 hours, the bonk will occur.

- Bonking is completely preventable.

Thanks for reading! Please let me know if you have any questions at derek@mountainridgept.com.