More spooky facts about skeletal health and bone stress injuries

/Bone stress injuries are a terrifying problem. On one hand it’s not the most likely issue to creep up on an athlete, but when it does, you’ll scream in fright as this silent terror unleashes its killing blow onto your training program.

“What is a bone stress injury?” you ask as you begin to quiver in your seat. Simply put, it’s bone tissue FAILURE due to repetitive mechanical loading. Initially, it could be recognized as swelling in the outer periosteal layer or in the marrow. Eventually, it can progress to a legitimate stress fracture.

Perhaps the scariest part about bone stress injuries isn’t the annoying fitness losses, it’s that bone stress injuries tend to be HIGHLY predictive of future bone stress injuries (600% increased risk in females, 700% in males) that ultimately result in further horrific setbacks. This is particularly the case in the 6-12 months following the first bone stress injury.

There are other bone stress injury concepts covered in this post here, but it’s such an important topic, and there’s so much to cover, let’s do another!

Cross training can kill your recovery

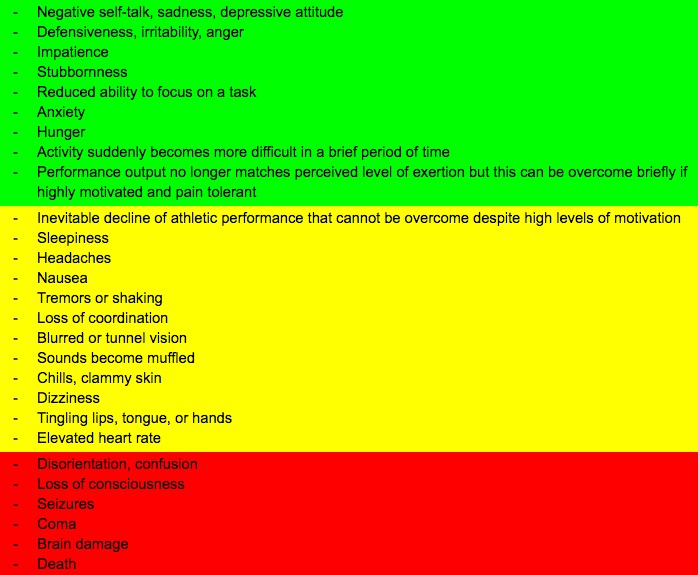

Finally admitting to having a bone stress injury, the injured runner convinces themselves it’s wise to cycle, row, swim, or step machine endless hours to *replace* the intentions of their usual running. Maybe they are afraid of gaining weight and feel obligated to burn calories. Or maybe they fear fitness loss and it’s an attempt to keep a cardiovascular base. Maybe it’s to maintain some sense of control and sanity. But beware…

While cross training can be a powerful tool when used wisely, there are runners who will try to work increasingly harder in intensity and attempt to accumulate more total time than they would ever typically run, thus deeply gutting their energy reserves.

Remember what causes many bone stress injuries in the first place? Insufficient caloric intake for the volume and intensity of running you were trying to make your body withstand. Bone health is a marker of overall metabolic health. A bone stress injury means the whole system is failing, often because it doesn’t have the energy to sustain the basic hormonal aspects of the physiologic equation. Burning through more calories with cross training than you would before the injury will compromise recovery, only digging further into your own grave.

Solution: chill out, bro. Don’t try to “make up” for the temporary loss of running. Be content with your ability to gradually reintroduce and slowly progress any aerobic activity. Consider this a clear message from your body that you weren’t training optimally. Overzealous cross training would continue to be a suboptimal strategy. Be patient, and you can safely resume running in a few weeks.

Impact forces aren’t the only force that bone must survive

Freddie Krueger wants you to believe that impact forces are the only bone loads that matter, but it’s not that simple. Much of the force encountered by a bone, like the lower leg’s tibia, is the direct result of muscle activity. Muscles are extremely powerful, so much so that they have the ability to subtly bend the long bones. This is particularly the case in the lower leg where the calf is designed to produce huge amounts of force. The bone is under high demand when running at any speed, but especially with fast running. Some bending is a good thing, because it activates the mechanosensitive structures to spur on adaptation. But too many bending repetitions in a short time frame can lead to a mechanical failure if the rate of bone destruction exceeds bone formation over a period of weeks to months.

Unless you like the feeling of a chainsaw hacking off your legs, heed these words. It’s important to address weaknesses in individual muscle groups. For one, heavy, slow strength training is a potent skeletal stimulus (and running isn’t). Loaded back squats, calf raises, deadlifts and so on, are all great methods to stress your bones while encouraging positive, anabolic hormonal shifts for the whole body. Furthermore, your scrawny muscles might not actually be strong enough to do their job in the first place, thus the bone exists in what could be considered an unprotected state.

Eventually, plyometrics like double leg and single leg hopping become a great bone stimulus too, because both the force and ground contact speed are high. In this context, the skeleton has a desire to make greater adaptations than during the slower ground contact times of running.

Intelligent pacing relates to the bone demands as well. In recovery from a bone stress injury, but also in prevention, runners need to be willing to truly slow down and run easy on days that have a primarily aerobic purpose. This allows the muscles to exert less force, which in turn dramatically diminishes bone stress. Anecdotally, the people that I know who have acquired stress fractures (and so many other injuries) all struggled with this aspect of training, always assuming that running slowly meant they weren’t achieving gains for the day, so they’d often end up in tempo or threshold mode. Let me be clear, you don’t have to push to make gains every day! Gains are made incrementally, from consistent training over a long period of time, with a routine, but occasional, sprinkling of higher intensity running.

Don’t let your sleep habits become a nightmare

You probably already know that short-changing your sleep can make you feel like Dracula sucked out 10 pints of your blood. But what you might not realize is that sleep is a critical time when growth hormone is released to help us recover from exercise, heal from injury, AND build bone. Bones are keen to remodel at this time, especially the bone formation side of the equation.

Miss a few minutes of sleep every once in a while - no big deal. Miss an hour or two most nights? That’s a big problem for many structures in the body that rely on a circadian rhythm, like the cardiovascular system, the endocrine system, the brain, and the skeletal system. As with many things impacting overall health, it comes down to what positive or negative behaviors you engage in, on average, day after day.

Sources:

Personal notes from University of Virginia Running Medicine Conference 2025

Personal notes from Decoding Running 2024

Sleep Disruptions and Bone Health: What Do We Know So Far?

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8244577/

UVA Running Medicine National Grand Rounds: Bone Health in the Runner with Adam Tenforde