Does foot pronation increase risk of injury?

/There is a misconception that certain structural features of the body are directly related to injuries. For years, people with lower arches were referred to as “pronators” and those with even flatter feet were “overpronators” or “hyperpronators.” They were all thought to have more injuries, and a portion of the shoe industry has really kept that mentality alive. The other two general foot types, neutral and supinated, were the supposed ideal.

Image Courtesy http://www.mikevarneyphysio.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/foot_pronation_supination.png

If you watched the pronator group walk, they might not appear to maintain their arch height very well. But is that always a problem? In the people labeled as pronators there are often joint structure differences that allow more inward collapse of the ankle and foot. In the supinator group there are joint differences that would keep the ankle and foot raised upward. Regardless of foot type, some level of pronation is a normal movement because it allows for shock absorption as the leg is loaded. A certain amount of supination is also normal because it allows for a rigid push off.

We begin our childhood with a lower inner arch height, largely due to a lack of bony structure, and this results in a pliable foot. With normal growth, as the foot bones develop, the inner arch tends to rise and the bones of the leg also change their orientation a bit. In some people the arch really doesn’t increase its height much with growth. And even if it does, in adulthood there can be contributing changes that would affect foot and ankle position:

degenerative or use dependent joint changes at front of the foot, the middle of the foot, or the rear of the foot

lower leg muscle shortening

weak, inhibited, or injured lower leg muscles or tendons (commonly the posterior tibialis)

general hypermobility throughout many of the body’s joints

tibia and femur bone structure (twisting, length discrepancy)

The concern is that these changes are also able to affect the movement of the knee, the hip and then even the pelvis and back. We all have a certain acceptable range of motion within each of these areas. If the changes in the foot allow the knee or hip to operate just on the edge of their tolerated position of use then, conceivably, you might have an increase in risk for knee or hip injury.

In actuality, foot structure may be more related to the type of injuries acquired than frequency of injury.

According to a 2001 research article in Clinical Biomechanics, higher arched runners developed injuries most often on the lateral side of the leg and had more ankle and bony injuries. Their lower arched counterparts had more knee and medial lower leg injuries.

A 2005 research article in the Journal of the American Podiatric Medical Association indicated that triathletes with a more rigid, high arch were at a higher risk of injury compared to neutral and pronated foot types.

More recently, in 2014, a meta-analysis in the Journal of Ankle and Foot Research indicated a very slight increase in risk of overall injury rate with the more pronated foot type being related to increased risk of kneecap pain and medial tibial stress syndrome (a.k.a. one of the types of shin splints.)

As you can see, the research is conflicting. The rate of injury is similar between athletes with all foot types. Perhaps we would have different results if we broke the common groups (pronator, neutral, supinator) down into subgroups based upon strike patterns (heel, midfoot, forefoot) to account for variations in demand.

My concern is that many of these studies assess the foot arch height while standing still. Unfortunately, this does not mimic how you use the foot in activity. Someone with a pronated foot structure while standing may not even touch their heel to the ground with running. Is it really going to be effective to put them in a motion control or stability shoe designed with a heel striker in mind?

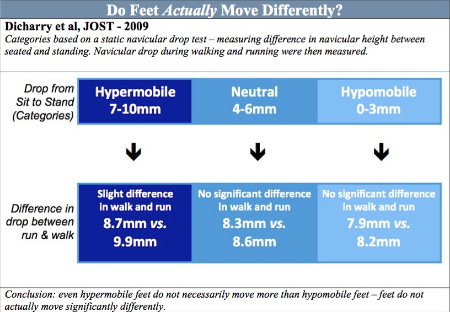

A 2009 study by J. Dicharry demonstrated that while running the total motion of the navicular bone in the arch isn’t drastically different regardless of foot type. They called the pronators the hypermobile group in this case. Even if the arch of a pronated foot is at a lower position in standing, it’s total amount of motion is only slightly increased from a neutral or supinated foot while running. Neutral and supinated feet were 0.3 mm different between walking and running. Pronated feet were 1.2 mm different from walk to run.

Should you be concerned with such minor differences and trying to use external devices like shoes to accommodate for them? The first step is to determine whether the pronation that is occurring is structural or a compensation. If forced to compensate, as in the case of decreased calf muscle length, you may need to focus on increasing mobility where it has been lost, like at the ankle joint, by elongating the calf muscles. Forcing mobility where it has already reached an excessive level in the midfoot by neglecting the calf length is not going to be helpful.

Our bodies are very good at adapting to gradually applied stresses, so a person with a more flexible, lower arch should be able to safely progress their activity just like anyone else. The research would suggest addressing the tissues that are the most likely to be injured with each foot type.

For instance, someone with a higher arch could focus on single leg balance and strengthening of the outer lower leg muscles. Those with a lower arch could focus on increasing strength of the inner lower leg muscles. I suggest we should focus on keeping both sides of the lower leg as strong as possible without one side becoming more dominant.

An often overlooked factor is inner foot muscle strength. Several of those muscles are meant to stabilize the arches of the foot, so it would be no surprise to me that decreased inner arch height can be associated with decreased muscle strength. But it’s not always a 1:1 relationship. Little research exists on this because it’s difficult to measure intrinsic foot muscle strength. Look for my blog article on intrinsic foot muscle strengthening soon.

Final thoughts:

Progress running intensity and duration in a safe manner using the 10% rule.

Keep the calf muscles loose to prevent ankle motion loss with a combination of rolling, massage, dry needling, and maybe stretching.

Strengthen the muscles that take the ankle and foot in all directions.

Strengthen the intrinsic foot muscles.

A pronated foot type does not necessarily require a bulky, stiff shoe and orthotics.

A pronated foot type is not going to be an immediate cause of injury, there are other factors to consider.

Don’t spend too much time worrying about your foot type because anatomical variation is normal.

Let your feet work how they were intended.

Geek out:

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19648718

http://www.japmaonline.org/doi/abs/10.7547/0950235

http://www.clinbiomech.com/article/S0268-0033(01)00005-5/pdf

http://jfootankleres.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13047-014-0055-4

http://journals.lww.com/cjsportsmed/Abstract/2001/01000/The_Role_of_Impact_Forces_and_Foot_Pronation__A.2.aspx

Please let me know if you have any questions at derek@mountainridgept.com and feel free to share this article via the share button below.